Power to the People: How You Can Empower Your Employees to Manage Micro-stressors

Between the global pandemic, outcry against systemic social injustice and brutality, and the drawn-out U.S. election results, we can all point to macro sources of stress that have left us totally exhausted.

The Institute for Corporate Productivity (i4cp), in collaboration with Professor Rob Cross, has been studying the myriad impacts of 2020, to include looking at the more subtle effects of sustained stress. For example, the million small, personal moments that are also contributing to our stress. These micro-stressors are the seemingly insignificant but stress-inducing relational touchpoints that accumulate quickly, slowly draining our personal, emotional and mental capacity until we find ourselves exhausted by the end of the day (if not earlier) with no clear reason why.

At work these micro-stressors might include sensing misalignment with a peer, misinterpreting an ambiguous client request, or having to coach a team-member. At home: a curt moment with a partner before work, a worrisome text from a child, or troubling news about an aging parent’s health.

Managers and leaders are caught in the crosshairs

Many organizations have tried to support weary employees by instituting regular 1:1 well-being check-ins with managers. But managers who ask reports how they are may find themselves facing an uncomfortable barrage of sensitive and personal issues that they are underprepared or unqualified to handle.

These same managers may be overwhelmed already with their own micro-stressors, leaving them little bandwidth to bear employees’ emotional burdens, too. Those who try to shoulder such stress alone will inevitably burn out.

Yet many organizations not only expect managers and leaders to support their employees through regular conversations, but also to be models of a relatively new imperative in business—well-being.

In a recent i4cp pulse survey, 59% of respondents said that leaders in their organizations are expected to model prioritizing their personal health and well-being. Of course, leaders themselves are common sources of stress for their employees, through destructive practices including poor communication and inconsistent behaviors that impact our sense of psychological safety at work.

When asked to share details of how leaders are modeling well-being at work, narrative responses from survey participants ranged from “pathetic” to “inspired.” Perhaps the most common response was taking time off and encouraging employees to do the same.

Better solutions benefit organizations and leaders

A best practice stress solution for organizations and managers, alike, is active communication— sending regular email reminders about the benefits of unplugging, leaders sharing their personal well-being practices in meetings, and push notifications on the intranet or IM channels.

A particularly promising approach involves creating supporting structures that make well-being activities part of the culture for everyone. For example, instituting no-meeting days or no-meeting during lunch hours, holding virtual walking meetings (as a much-needed reprieve from video calls), or holding team meditation/mindfulness sessions to kick off meetings, means employees aren’t left to their own devices to model their leader’s behaviors. Instead, they take part in team behaviors that reinforce well-being for all.

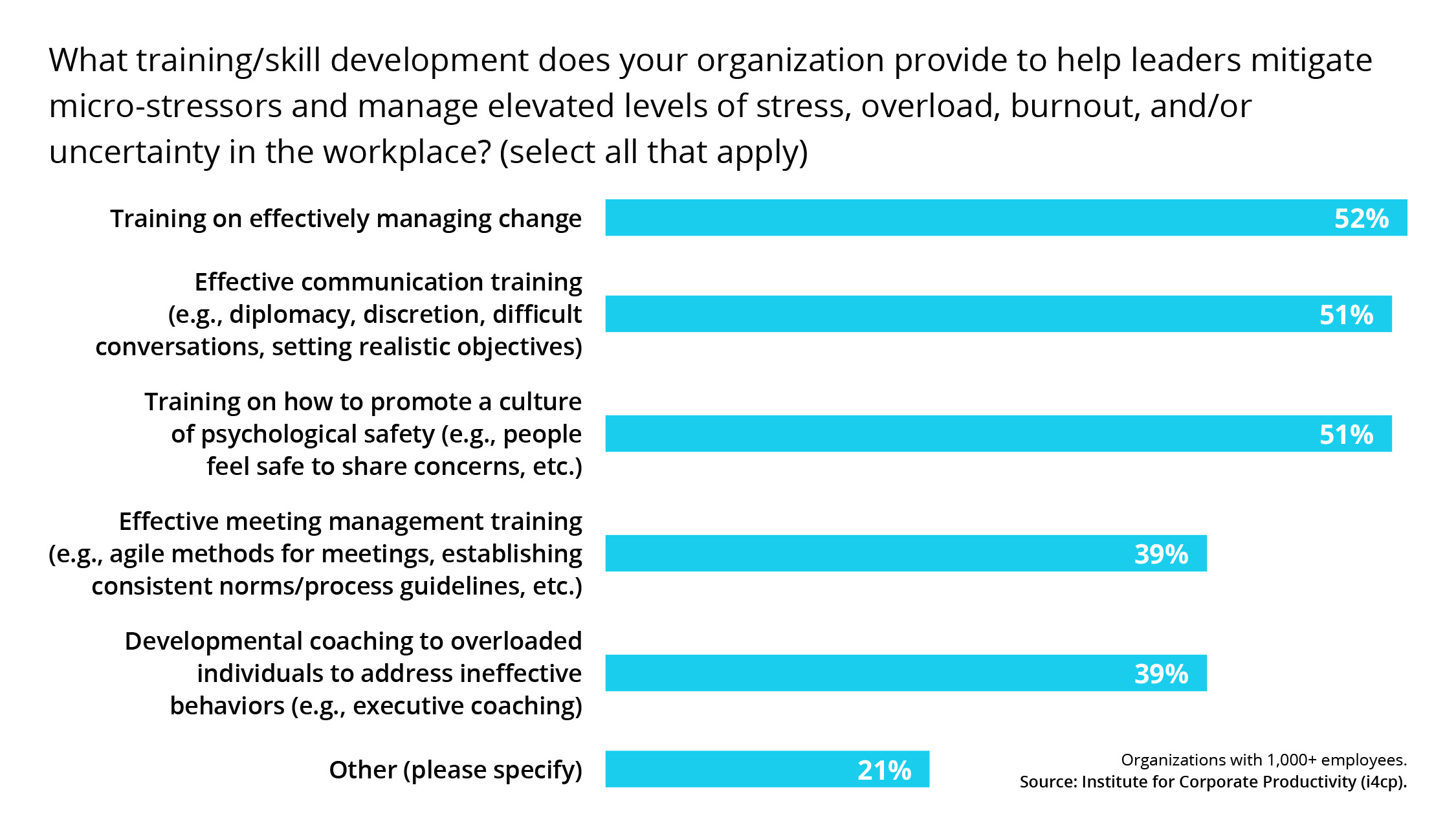

Clearly, more leaders and managers should engage in shaping team norms in such constructive and well-being-supportive ways. To help managers address micro-stressors, the pulse survey results indicate that most large organizations offer training on change management and effective communication, along with promoting a culture of psychological safety, though smaller organizations may have fewer formal resources to do so.

Further, those common programs often fail to fully address the velocity and volume of micro-stressors that managers face today, and may focus on making personal changes that don’t realistically account for the demands of interconnected environments and relationships.

Beyond the formal training and vacation reminders, we must ask what behaviors are actually being incentivized? If there is a persistent culture of long hours and wearing burnout as a badge of honor, then even the most sophisticated programs are unlikely to provide support. In fact, underutilized well-being programs do more harm than good since a stigma builds around using them at all.

When asked how leaders are incentivized to prioritize their own health and well-being, many respondents were stumped, offering such responses as “it’s mandated in words, but no behavior." However, a notable example points not to a single incentive, but a “solid culture of accountability around self-care” that is reinforced by recognition in global town halls with prizes and celebrations for individuals and teams that show improvement.

The global pandemic has forced organizations to be more mindful of employee well-being, primarily by implementing interpersonal check-ins between employee and manager that bring to light the range of micro-stressors impacting individuals in the blurring environment of work and home. But managers (who face many micro-stressors themselves) bear the brunt of this emotional labor.

The answer? We must look to models that use better communication and effective training to help build individual and team resilience. Instead of overwhelming leaders with hefty asks, we need to empower all employees by establishing and evolving cultures of collective support that emphasize sharing the responsibilities of self and team-care.